- Ãëàâíàÿ

- Àâèàöèÿ è êîñìîíàâòèêà

- Àäìèíèñòðàòèâíîå ïðàâî

- Àêöèîíåðíîå ïðàâî

- Àíãëèéñêèé

- Àíòèêðèçèñíûé ìåíåäæìåíò

- Áèîãðàôèè

- Àâòîìîáèëüíîå õîçÿéñòâî

- Àâòîòðàíñïîðò

- Êóëüòóðà è èñêóññòâî

- Ìàðêåòèíã

- Ìåæäóíàðîäíîå ïóáëè÷íîå ïðàâî

- Ìåæäóíàðîäíîå ÷àñòíîå ïðàâî

- Ìåæäóíàðîäíûå îòíîøåíèÿ

- Ìåíåäæìåíò

- Ìåòàëëóðãèÿ

- Ìóíèöèïàëüíîå ïðàâî

- Íàëîãîîáëîæåíèå

- Îêêóëüòèçì è óôîëîãèÿ

- Ïåäàãîãèêà

- Ïîëèòîëîãèÿ

- Ïðàâî

- Ïðåäïðèíèìàòåëüñòâî

- Ïñèõîëîãèÿ

- Ðàäèîýëåêòðîíèêà

- Ðèòîðèêà

- Ñîöèîëîãèÿ

- Ñòàòèñòèêà

- Ñòðàõîâàíèå

- Ñòðîèòåëüñòâî

- Ñõåìîòåõíèêà

- Òàìîæåííàÿ ñèñòåìà

- Òåîðèÿ ãîñóäàðñòâà è ïðàâà

- Òåîðèÿ îðãàíèçàöèè

- Òåïëîòåõíèêà

- Òåõíîëîãèè

- Òîâàðîâåäåíèå

- Òðàíñïîðò

- Òðóäîâîå ïðàâî

- Òóðèçì

- Óãîëîâíîå ïðàâî è ïðîöåññ

- Óïðàâëåíèå

- Ñî÷èíåíèÿ ïî ëèòåðàòóðå è ðóññêîìó ÿçûêó

- Äðóãîå

Êóðñîâàÿ ðàáîòà: Attaction of foreign inflows in East AsiaÊóðñîâàÿ ðàáîòà: Attaction of foreign inflows in East AsiaRUSSIAN STATE PEDAGOGICAL UNIVERSITY BY HERZENEconomic facultyDepartment of applied economy Course work on theme: ATTACTION OF FOREIGN INFLOWS IN EAST ASIA Student of the third course _________________ Superviser of studies, Candidate of economic science, Senior lecturerLinkov Alexei Yakovlevich St. Petersburg2000 y. Plan 1. Integration, globalization and economic openness- basical principles in attraction of capital inflows 2. Macroeconomic considerations 3. Private investment: a) Commercial banks b) Foreign direct portfolio investment 4. Problems of official investment and managing foreign assets liabilities 5. Positive benefits from capital inflows International economic organizations (IEOs), such as the World Bank, the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), have bun promoting economic openness and integration, centered on free trade and capital flows. as not a complement but a substitute for national development strategy. Investment efforts in South Korea and Taiwan were underwritten by active government strategy, including subsidies, promotion, tax incentives, socialization of risk, and establishment of public enterprises. Singapore’s economic growth was also predicated on a high investment strategy implemented by the government, even though Singapore relied relatively more on foreign investors than the other East Asian countries did. Regionalism is likely to remain an important factor in global economic relations in the foreseeable future, as countries continue to strive for greater access to foreign markets and for solutions to economic problems and disputes that in many cases might be resolved only through regional cooperation. Managing large and perhaps variable capital inflows- or, more aptly, managing the economy in such a manner as to effectively and productively absorb these flows- is a major challenge for East Asian countries. Each country has embarked in its own financial markets, following initiatives in trade liberalization. Until recently, the bulk of capital inflows in East Asia has been FDI and project- related lending, both official and private. At the relativly lower levels of a decade ago, these flows could be readily accomodated. The overall impact of foreign investment on growth and exports has been very positive. As the capital flows have increased, they have created macroeconomic pressures on exchange rates, domestic absorption, investment policies, and the capacities of domestic capital markets. The more recent expansion of portfolio investment implies much more integration into global capital markets and a corresponding increase in exposure to international market discipline- refferred to by some as market- conditionality- that will circumscribe policy options and limit the range of possible deviation from global norms on a number of variables. The increased complexity of these poses serious policy challenges to authorities, whose primary objective is to promote real sector growth in economies in which the industrial and financial sectors are still rapidly evolving. Achieving sustainable, rapid growth with open capital accounts and active capital markets my will be more difficult than was true with the more closed financial structures that used to be the norm in East Asia. Indeed, concern about losing control of domestic policy contributed to some governments reluctance to liberalize their financial sector and capital accounts in the past, and contributes to their willingness to stop the process if they see it getting out of hand. However, capital controls are becoming more porous, the pressures to liberalize stronger, and the benefits from more open financial sectors more compelling Government preferences and market forces are liberalization. East Asian countries can continue their rapid growth only if they achieve the efficiency gains that result from further liberalization. Furthermore, less distorted markets provide fewer opportunities, for sent-seeking behavior and resource misallocation caused by price and other market distortions. As capital, domestic and foreign, to seek the highest rate of return in only market. Investment levels in countries that offer strong growth potential can be augmented by flows of foreign saving. At the same time, sophisticated investors have expanded opportunities to seek short-term gain from exploiting market imperfections, implicit guarantees, and price fluctuations. These latter activities and the extent to which they influence other portfolio investments are more worrisome because of their volatility and their potential impact on long-term policy. They may or may not be responding to fundamentals. Theoretically, speculation and arbitrage are believed to contribute to efficient markets and to impose few net costs overall. Market forces represented by these speculative flows have generally, but not always, created pressures toward needed corrections, either of fundamental policy unbalances or of unwarranted implicit guarantees or distortions. However, short-term traders can exert a great deal of influence on specific markets as specific times, with can work against government policy objectives. It is argued that short-term traders would do this only if policies were wrongheaded, but in practice market forces make no judgments as to the inherent value of a policy- only as to whether a profit can be made from expected market movements. Market agents have been known to err and overshoot (although policymakers probably anticipate or perceive more errors than are likely to occur). Nevertheless, it is not generally wise policy to try to resist market pressures on the theory that they may be wrong. They are not often wrong, and resistance can be expensive, since today private international markets can mobilize vastly larger sums than even industrial country governments. When market forces do err or overshoot, they correct themselves usually quickly enough to avoid much lasting harm. In fact, quick policy reaction when the market is applying pressure in response to some perceives profit opportunity often sends a signal that large gains are unlikely and mitigates the flow, whereas digging in against market trends may set up an easy win for speculators at the government’s expense. Moreover, where policy failures contribute to market pressures, resistance to adjustment can be vary expensive. The burden is on governments to manage their economies so that easy arbitrage opportunities are not readily available and official policies or actions do not give rise to implicit guarantees or other distortions that markets can exploit to the detriment of public objectives. Consistent application of sound policy and clear direction goes a ling way toward reducing the likelihood of overreaction by markets. In addition, policymakers can blunt short-term flows that pose dangers to the economy through a variety of instruments that reduce speculative short-term gains. Governments should naturally exercise caution in opening financial markets to international flows. Liberalization needs to be predicated on (a) developing an appropriate regulatory framework and supervisory system, (b) ensuring that the resulting incentives promote prudent behavior, and (c) adopting a macroeconomic policy structure that is consistent with open financial flows. Policies need to promote both domestic and international equilibrium, be flexible enough to respond to disturbances from the capital markets, and include safety features to activate in periods of crisis. Even with such precautions, the world is a highly uncertain and unpredictable place. There can be no assurances against unforeseen crises, even with the best of policies. This is part of the price of open market economies. The point is not to stifle an the economy in order to avoid crises but to ensure that the economy is sufficiently flexible and robust to weather the crises and continue to develop and liberalize despite such interruptions. The basic the theoretical framework for analyzing the impact of external capital flows derives from the pioneering work done by Flemming (1962) and Mundell (1963) on open- economy stabilization policies. Their relatively simple models have been revised as the issues addressed have become more complex. Policy guidelines have become more complicated and much more dependent on a host of other factors that affect economic activity, including expectations, which can be hard to pin down. The theory provides a useful backdrop and guide for appropriate policy responses, but practical policymaking requires a thorough understanding of the characteristics of the economy in question, the exact nature of the capital flows, and the range of available policy options and tradeoffs. East Asian policymakers have been adept at pursuing reform until difficulties arise, then slowing or even backtracking a bit to reassess and make corrections before moving ahead once more. This pragmatism has proved its worth, as these countries have generally avoided major crises. The basic theoretical models were initially developed to study the relative effects of monetary and fiscal policies in achieving domestic stabilization. Impacts on the external equilibrium were viewed as results and perhaps as constrains. Critical to the analysis if the exchange regime- fixed or floating- and the openness of the capital account (or the degree of substitutability between domestic and financial capital assets). Under most conditions, the models indicate, that given a fixed nominal exchange rate regime, fiscal policy is relatively more powerful than monetary policy in affecting domestic output. Expansionary fiscal policy increases demand for domestic goods but also tends to raise interest rates as additional public borrowing is required. Higher interest rates attract more foreign capital, increasing reserves. The increase in domestic resources to that sector. The current account balance deteriorates, partly absorbing the increased capital flows. Real currency appreciation occurs as domestic prices rise, even though the nominal rate if fixed. Conversely, monetary policy has a greater effect on the external account. Raising domestic interest rates attracts foreign capital and builds reserves, the amount depending on the substitutability of foreign and domestic assets. Attempts to stimulate domestic demand by lowering interest rates are diluted, as capital flows overseas to seek higher rates there, reducing any effect on domestic demand. The more substitutable foreign and domestic assets are, the less the interest rate change required for a given effect. Increased substitutability of assets leads to other problems, however. Where governments try to constrain domestic demand by raising interest rates, capital flows in, to benefit the higher rates, and counteracts the restraint. If sterilization is attempted- if, for example, governments sell bonds (tending to further increase domestic interest rates) to absorb the increase in the money supply associated with the influx overwhelm the authorities’ ability to continue to issue bonds to purchase foreign exchange. In such circumstance, it is hand to prevent a real currency appreciation. For an economy dependent on export growth, as most East Asian countries are, the dangers of expansionary fiscal policy, combined with monetary constraint to keep inflation under control, are evident. East Asian countries generally adopt more conservative fiscal stances than Latin American countries. Under a floating-rate regime, the additional exchange rate flexibility dampens some of these effects, but at the cost of loss of control over the nominal exchange rate. Fiscal policy becomes relatively lass effective in influencing domestic output. The increase in demand from expansion leads to an appreciation of the nominal (and, consequently, the real) exchange rate, increased imports and lower exports, and less demanded for money and bonds. Interest rates rise, but less than in the fixed-rate case, and the floating rate keeps the external accounts in balance. The increase in capital inflows offsets the higher current account deficit. Under most reasonable assumptions, output rises, but less than under a fixed exchange rate for a given increase in expenditures. By contrast, monetary policy can have a more compelling effect. An expansionary action, such as open market purchase of domestic bonds, increases output through the effects of money supply on demand. It also leads to a depreciation, which shifts resources to the tradable sector and decreases the current account deficit, offsetting the outflow of capital brought about by the more perfect substitutability of assets, although the interest rate change will be smaller. These models can also be used in reverse to examine the effects of a change in external variables on the domestic economy. What are the implications when we look at the effect on domestic policy of increases in foreign capital inflows? For a regime with a fixed nominal exchange rate, an increase in foreign inflows tends to reduce the domestic interest rate and increase domestic demand. This, in turn, leads to an increase in domestic prices that will bring about a real appreciation through higher domestic inflation. Reserves tend to accumulate, although by less than the capital inflows, as the current account also deteriorates. Monetary policy action to absorb the capital inflows through, for example, open-market sales of bonds (sterilized intervention) could offset the impact on demand. But such an action would tend to increase interest rates, which could well attract more capital inflow. It is not likely to be effective in the long term if there are practical limits on how many bonds can be issued, and it could be costly (because of negative carry on the reserves accumulated). The more substitutability there is between domestic and foreign assets, the less variance is possible between domestic and foreign interest rates before increase in the domestic interest rate become self-defeating. Fiscal contraction would offset the increase in demand and perhaps allow a reduction in interest rates, which would diminish the attraction of domestic assets to foreign investors. A fiscal response would take longer to orchestrate than a monetary response, however, become public budgets are hard to cut in the short run. Under a floating-rate regime, a foreign capital inflow leads directly to an appreciation of the nominal and real exchange rates. The impact on output depends on the relative strengths of the increase in demand resulting from the capital inflow and the reduction in demand for domestic output because of the appreciation, but an increase in output is likely. If the exchange rate is allowed to adjust, the real appreciation attributable to the capital inflow has less effect on the domestic economy. Prices may rise, and interest rates may fall. However, for export-oriented economies a sustained appreciation may pose serious long-term problems for the export sector. Many fear that appreciation would cause significant loss of exports and eventually overall growth, as markets are lost to lower-cost competitors. Depending on the relative strengths of different effects, the expansion of domestic demand could be counteracted by either tighter fiscal policy or monetary contraction, offsetting some of the appreciation. The former still raises the same questions about the speed of response; the latter may raise interest rates enough to attract more foreign inflows, exacerbating the initial problem. Furthermore, exchange rate appreciation induced by capital inflows will increase the yield to foreign investors as measured in their own currencies, which may extend the capital inflows, particularly short-term, yield-sensitive flows. The ability of floating exchange rates to insulate an economy from external influences depends on the authorities’ willingness to accept exchange rate movements determined, in part, by foreign investment demand. A floating-rate regime also depends on the flexibility of domestic prices and wages and on adequate factor mobility to be effective. The prevailing fixed or managed exchange rate regimes in East Asia and most other countries indicate a marked reluctance to accept the implications of fully floating exchange rates. Even at this simple level, the models illustrate several important points. The degree of openness of the capital account and the substitutability of foreign and domestic assets have an important bearing not only on financial sector policies but also on real sector policies. Financial flows can have tremendous effects on the real economy – for example, on interest and exchange rates and, through those variables, on output, employment, and trade . The more open an economy and he more integrated into world capital markets, the harder it is for the country to maintain interest rates that deviate significantly from world rates or an exchange rate that is far out of line with what markets believe to be proper. The market’s views on these rates are driven by many short-and medium-term considerations and, particularly for interest rates by forces in the major financial markets. Market pressures on a given country’s capital markets reflect a great deal more than just the fundamentals of a particular country. Countries cannot afford to have key policy variables that are inconsistent with global trends. Thus the capital account’s openness exposes the economy to pressures that may complicate achievement of the country’s long-term real sector objectives, and stabilization issues must be more finely balanced against growth objectives. Integration into capital markets has its price. To be more realistic in these models, one can admit leakage’s and other factor- such as unemployed resources, market imperfections, and expectations- that may mintage or enhance the basic impacts described above. Introducing greater sophistication increases the complexity and number of variables that must be considered in reaching any conclusion, but it does not make reaching a conclusion any easier. In fact, the results can be less determinant. The amount of unemployment in the economy affects the extent to which changes in aggregate demand move output or prices. In developing economies with limited factor mobility among sectors, the question of unemployed resources may have to be considered on a sectoral as well as an aggregate level, or by skill level. Depending on the particular model used, the inclusion of expectation function private investors will apply to any government action or nonaction. In some cases, where governments have announced a commitment to protect exchange rates or fix interest rates, guesswork is reduced for the market, but possibly at the cost of offering privat speculative investors a largely covered bet. In other cases it is much harder to predict whether a policy course outlined by a government will be seen as credible. In factor in a policy’s effectiveness. The history of government commitment and the market’s estimation of the resources the government has available to defend a position figure into this equation. Although models provide useful general guidance and help frame the issues, their implementation must be tempered by an analysis of the features of practical considerations. The basic dilemma stems from the role of the exchange rate (nominal for-term transactions and real for long-term decisions) in equilibrating both goods and capital markets as they become more open. Heretofore, developing countries in East Asia and elsewhere have been able to use the level and movement of the exchange rate to effect the goods market almost exclusively. East Asian countries have often used nominal deprecations to maintain stable or slightly falling real exchange rates and so promote exports. As capital markets open capital flows can create pressures to appreciate the real or nominal exchange rate against targets directed toward the goods market. Attempts to maintain a rate satisfactory for the goods market without adjusting other policy instruments can lead to disruptive capital flows. Either the exchange rate target has to be modified, or other policy instruments must be adjusted. Using the exchange rate as a “nominal anchor” to help combat inflation adds to the burden and can be effective only where fiscal and monetary policies are closely coordinated in support of that objective. In countries with less developed financial sectors, the choice and range of instruments are limited. As the theoretical models have become richer and more complex, so have the range and complexity world. Most of the stabilization models deal with money and simple bonds as assets and include little, if any, explicit analysis of risk- except as the degree of substitutability of domestic and foreign assets may be taken as a partial proxy for differing risk. The models do not look at the differential impacts of different types of capital flow can be quite different. Policymakers need to look at the characteristics of the instruments involves in capital movements in both a short-term and a medium-term perspective to help formulate policy. Commercial bank borrowing provides resources that are essentially untied. Where the capital flow is directly linked to a specific project, its impact will be in the capital goods markets. It will probably have a high import content, witch will absorb a portion of the increase in demand from the capital inflow and ease pressure to appreciate the exchange rate or raise domestic prices. However, because these flows are flexible, they can readily be used to finance budget shortfalls of the government or of enterprises, perhaps delaying necessary fundamental adjustment, as often happened leading up to the debt crisis of the 1980s. In that case they increase aggregate demand and are more likely to lead to inflationary pressure and exchange rate appreciation. Because of its fixed term, the stock of this form of capital is not likely to be volatile. However, flows can stop abruptly, leading to economic stresses, particulary where borrowers have come to rely on foreign flows and have allowed domestic savings to decline. Excessive dependence on commercial bank flows can be risky because there are few built-in hedges to protect the borrower against exchange and interest rate fluctuations. Furthermore, repayment schedules are fixed in foreign exchange, and provision must be made to service this debt on schedule, regardless of the state of the economy of then project financed. Foreign direct investment initially affects the market for real assets through purchases of new capital goods and construction services for plant constructions and sales of firms to foreign investors, or, in the case of privatization’s and sales of firms to foreign investors, through purchases of existing plant and equipment. Direct investors may even encourage incremental national saving and investment, either from local partners or from bank borrowing. FDI in new plant increases the aggregate demand for investment goods, and frequently of other goods as well. Higher demand for imports eases the pressure of capital inflow on the domestic, reduces reserve accumulation, and relieves pressure on the exchange rate. Most FDI in East Asia has been of this productive type, and its impact has been manageable. When FDI is in a protected industry, as has occurred in some cases, the profits it earns may not come from real (as opposed to accounting) value added. This form of FDI is least beneficial, as it exploits local marker imperfections to the advantage of the foreign investor and may not increase domestic value added or measured or wealth measured in world prices. The eventual repatriation of capital and profits could reduce the host real income and wealth. FDI attracted by privatization programs is not as likely to result in much new investment. (Depending on the terms of sale, the new owner may be required to undertake a certain amount of new investment or renovate existing equipment). When an existing domestic asset is sold, there is no direct increase in the capital stock, although the productivity of the existing capital should increase. FDI received is available for whatever purpose the seller chooses, including reducing an external gap, lowering taxes, or sustaining other current expenditures. The effect depends other current expenditures. The effect depends on what the seller (the government, in the case of privatization, or a private, in the case of a private asset sale to foreign interests) does with the proceeds: reduce other debt (which might ease pressure in the banking system), invest in another project (which would increase investment, as discussed above), or spend on other goods, primary consumption (which would increase aggregate demand and perhaps imports, with no increase in output capacity). To the extent that capital inflows support increased imports without a corresponding increase in investment, domestic saving are reduced. FDI lows are as sustainable as the underlying attraction- stable policies and profitable opportunities. To the extent that an economy’s growth depends on a sustained inflow of FDI- for the level of investment, for technology and skill transfer, or for supporting an export strategy- the importance of maintaining those conditions is evident. Although FDI is not readily reversible, sharp drops on new flows can have repercussions if countries depend on it for future export growth. Similarly, to the extent that countries have increased resources derived from the foreign investment, a reduction in those flows will require perhaps difficult adjustments on the consumption front. No contractual repayments are associates with FDI. Investors expect a return on their investment- generally a higher rate of return that on loans and bonds because of the higher risks and opportunity costs involved. Malaysia, which has been the beneficiary of substantial FDI, has grown rapidly: an estimated one- third of its current account receipts is now claimed by service payments on FDI. When FDI flows are sustained over a long period, foreigners inevitably came to own a substantial portion of the country’s capital stock in the sectors that attracted FDI. This prospect is not viewed with as much concern as it once was FDI is not likely to be volatile: once invested, the real asset is not going to more, although changes in ownership are possible. Eventually, a foreign investor may want to sell to a local partner or divest onto a local stock market, and the host country needs to be prepared for a repatriation of capital. In times of stress, however, investor may well find ways to get their capital out quickly. Many investors set as a target the recouping of their outlays (which are usually less than total project cost) within two or three years, through repatriated) profits.

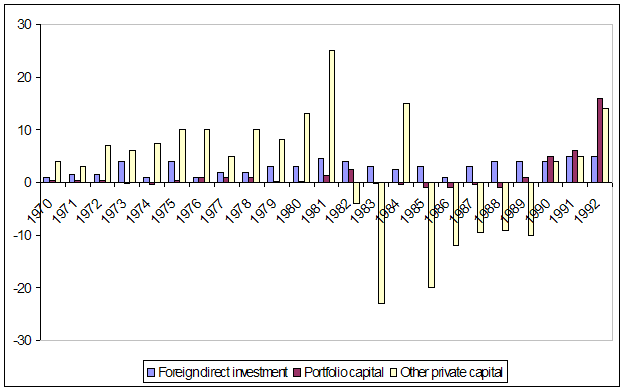

Composition of Net Private Capital Flows (in billions of 1985 U.S. dollars)

FPI potentially has a much wider range of effects, depending on the type of instrument and how it is used. It can occur through securities placed in foreign or domestic markets, including short-term funds and demand deposits. (The relation of these two instruments to physical investment may be limited; they may be much more a function of financial variables). Although many of its impacts can be similar to those of bank loans and FDI, portfolio investment can also have a much greater effect on domestic capital markets and interest rates. Whereas direct investment regimes, portfolio flows raise issues of financial and capital market regimes and their management. Portfolio investment touches more on issues of disclosure, accounting, and auditing that does direct investment. When portfolio investment takes the form of an external placement (bond or equity) and the funds are used to finance new investment, the effects are in the real sector, as discussed for FDI. If the funds are used for other purposes, the result depends on those purposes. Paying down debt might ease pressure in the banking sector or build reserves. If the inflow is subsequently invested in domestic capital markets or deposited in banks, the money supply and domestic credit expand. Demand for assets, including real estate, would probably increase, with effects similar to those of foreign investment in local markets (discussed below). If the funds are used for consumption, pressure on domestic output could increase, leading to a rise in prices. These uses are likely to put more upward pressure on the exchange rate and downward pressure on interest rates, as the prices of nontradables and domestic assets are bid up. This is true whether the government or the private sector carries out the initial borrowing or stock issue. Offshore placement do not give rise to volatility concerns in the issuing country’s market. Subsequent trading in the asset occurs in the foreign market and does not result in further capital movements, other than normal repayments, into or out of the borrowing country. Sustained access to foreign markets if another matter; if depends on the market’s continued positive assessment of the borrower, the liquidity of the borrower’s paper, and the borrower’s compliance with market rules. If circumstances lead to price volatility in foreign markets, new placements will be inhibited. In some East Asian countries (Indonesia, Korea, and Thailand) domestic banks have been major issuers of bonds into external markets. Since 1990, 40 percent of placements have been by financial institutions, with banks accounting for 27 percent. Large banks obviously have better credit rating than many of their clients and are thus able to raise funds less expensively. This is a legitimate intermediation function and has opened financing opportunities to many domestic firms that would otherwise have had less access to funds. For the ultimate borrower, lower interest rates, not foreign exchange rates, are typically the critical factor. For the intermediating banks, the spreads and volumes are attractive, and the operations help establish the bank’s international presence. These actions, however, pose two risks. First, there may be a relative decrease in the effectiveness of monetary police, since in the effectiveness of monetary policy, since the financial system can miligate or offset government attempts to expand or contract credit by modulating its foreign borrowing for domestic clients. When foreign interest rates are lower than domestic rates, borrowers will be tempted to seek more funds abroad, which may undermine domestic policies of monetary restraint. Second, banks (especially public or quasi-public banks) may be borrowing abroad with the implicit or explicit expectation of a government quartette. They may not take full account of the exchange risk and may face interest risks as well, since they are intermediating across currencies and between short-term liabilities and long-term assets. These risks are likely to be passed on to the government, should they adversely affect the banks. The recently reported instance of BAPINDO, a troubled Indonesian bank that borrowed internatinally, seems to have involved an implicit guarantee, as that bank would not have been able to borrow on its own account. More generally, central banks may be forces to intervene to protect the banking sector with official reserves if there are major disruptions of commercial banks’ capacity to refinance abroad. For some large borrowers, domestic markets may not yet be deep enough to absorb the size and other requirements of their financing needs, so that these enterprises must turn to international markets. FPI in domestic markets is a different matter. The bulk of this inflow has been in equities, as investors have been seeking high yields, mostly through appreciation. These flows purchase existing portfolio assets and sometimes new issues. To the extent that the new issues fund new investment, the effects would be quite similar would be owned by the domestic issuer rather than the foreign investor. New issues may also be used to recapitalize existing operations. Here the effect would be through the banking system and the rest of the domestic financial market, where debt would be retired by the new equity-generated flows. Although this could ease pressure on the banking system, it would tend to lower interest rates and increase domestic liquidity. That, in turn, would increase aggregate demand and create more pressure on the exchange rate than if the funds had been invested in new equipment with a high import content. The bulk of equity investment has been into existing stocks in East Asian markets, driving up the prices of equity. the cost of capital drops for those floating new issues, but there are for also strong wealth effects on existing asset holders- as their wealth increases, consumption is likely to go up as well. This will tend to raise domestic prices and appreciate the currency in real terms, Whether these foreign equity, investments increase physical investment depends on the behavior of the other asset holders- those who sold to foreign investors and those whose assets appreciated. If they invest in new projects, physical investment will also increase, otherwise, it will not. It is more likely that domestic savings will fall when there are large portfolio investment flows than when the flows take the form of FDI. In Latin America, which has experienced more portfolio inflows decline, rather than physical investment to increase. In the past East Asia has avoided this result, partly because its overall policy regime has favored investment, partly because of the greater degree of sterilization it has been able to achieve, and partly because the share of portfolio investment has been smaller. Portfolio flows are a very recent phenomenon, and it is still to soon to measure many of their effects in East Asia. It is particularly worrisome when large private capital flows move into commercial real estate. Experience in many countries, both industrial and developing, indicates the ease with which speculative bubbles can develop in real estate during an investment boom. Asset inflation in this sector can generate very high rates of return- much higher than are available from investment in manufacturing- over a few years. But such rates are not sustainable. When the bottom falls out, as it inevitably does, there are frequently severe repercussions on the banking sector, since domestic banks are usually major financiers of the real estate, and governments often end up bailing out the financial sector. Indonesia faced this problem in 1993; Thailand saw carliev bouts of these bubbles; and they are not unknown in other countries, including the United States and Japan. The sustainability of flows into stock markets is a complex matter. To the extent that the flows depend on continued high gains, mostly appreciation, one could wonder whether the high of return of 1992-93 will resume after the 1994 correction. Even in the best of circumstances, one would expect some flow reversals, in addition to normal volatility. Unfortunately, the best of circumstances rarely occurs, and the Mexican episode of December 1994 has precipitated outflows in many emerging markets as fund managers have bailed out everywhere. It is hard not to view this as herd behavior with a tinge of panic, but it caused a 3 percent devaluation in Thailand and more than doubled short-term interest rates there. Other East Asian markets have also suffered outflows as international investors have generally reduced their exposure in emerging markets. However, giver the long-term growth potential of the East Asian economies and the indications of a longer-term stock adjustment process, there is reason to except that such reactions will be temporary set backs in a persistent trend toward a lager share of sound emerging market stocks in global portfolios. The spectacular yields witnessed recently may not be sustainable, but the East Asian countries should offer high rates of return over the long term and should continue to attract investment. A number of countries in East Asia and elsewhere have begun attracting foreign portfolio investors into their own fixed-income markets ,purchasing, instruments in local currency. In this case the foreign bondholder takes the exchange risk, for which he expects added compensation. It is encouraging that these economies are becoming attractive enough, and their exchange management is considered stable enough, to attract investment in local currency securities. For obvious reasons, interest tends to be in bank deposits, in shorter maturities, and in guaranteed instruments of government or their agencies. To the extent that short-term capital flows exceed working balances, trade financing, or bridge activities to long-term investment, they are most likely the result of relatively high interest rates not offset by an expected devolution. For the most part, these flows are seeking high short-term rates of return and reflect cash management or speculative decisions rather than long-term investment decisions rather than long-term investment decisions. But like long-term flows, they tend to lower domestic interest rates and appreciate the exchange rate. They are likely to expand bank reserves and lead to more credit expansion, although on a potentially more volatile base. To the extend that a government is trying to restrain domestic demand with high interest rates, the inflow would undermine its policy. These flows may not directly influence long-term savings and investment, but they may do so. The World Bank and investment bankers regularly provide advice to developing countries on asset and liability management. But that advice often is non optimal or simply wrong. Although many tactical tools for active risk management in developing countries have been developed in the past decade, a framework for developing a strategy that incorporates country-specific factors has lagged far behind. For example, in case when the Federal Reserve Bank (the “Fed”) last September arranged a $3.6 billion bailout of Long Term Capital Management (LTCM)- a Connecticut- based hedge fund- critics of the US financial establishment cries foul. The bailout contrasted strikingly with IMF treatment of indebted firms in Asia. When indebted businesses in Asia were unable to replay foreign loads, US and IMF officials insisted that they be forced to close and their assets sold off to creditors. Bailing out ailing businesses with endless lines of bank credit was, US officials claimed, the essence of “crony capitalism” and the cause of all Asia’s problems “Reducing expectations of bailouts, ” declared the IMF, must be step number one in restructuring Asia’s financial markets. To Japanese officials, the LTCM bailout was a clear case of the US “ignoring its own principles”. Representative Bruce Vento (Democrat, Minnesota), in a Congressional investigation of the LTCM bailout, said that “there seem to be two rules, a double standard.” But this view is incorrect. Where bailouts are concerned, there is only one standard. Whether in Korea, Thailand, Connecticut or Brazil, US- and IMF- organized bailouts conform, to the same quiding principle: whatever happens, whoever is at fault, the wealth of Western credits must be protected and enhanced. Until 1997, Western creditors were bullish on Asia and “emerging markets” generally. They poured billions into stocks, banks and businesses in Thailand, Indonesia, Korea, expecting mega-returns and a piece of the action as the former “Third World” embraced freemarket capitalism. Beginning in 1997, though, Western investors began to worry that they might have over-lent. They pulled out of Thailand first, selling baht for dollars; as the baht’s value collapsed, worry turned to panic. Soon, international financial operators were selling won, ringgit, rupiah and rubles in an effort to cut potential losses and get their funds safety back to Europe and the US. In the ensuing capital flight, Asian stock prices plunged and the value of Asian currencies collapsed. Local businesses that had taken out dollar payments to Western creditors. For a time, local governments tries to stave off default by lending their reserves of foreign currency to indebted firms. South Korea used up some $30 billion in this way. But this money soon ran out. Western banks refused to make new loans or roll over old debts. Asian businesses defaulted, cutting output and laying off workers. As the economies worsened, panic intensified. Asian currencies lost 35 to 85 per cent of their foreign- exchange value, driving up prices on imported goods and pushing down the standard of living. Businesses large and small were driven to bankruptcy by the sudden drying up of credit; within a year, millions of workers had lost jobs while prices of basic foodstuffs soared. As the crisis unfolded, IMF officials flew to Asia to arrange a bailout, agreeing ultimately to loan $120 billion to Thailand, Indonesia and South Korea. When announcing these loans, the press used terms like “emergency assistance” and “international rescue package,” leading the casual reader to presume that the money will be spent on food for the hungry, or aid to the jobless. In float, the money is used to “help” countries pay bank their debts to international banks and brokerage houses. Which international banks and brokerage house? The same ones who made speculative loans in the first place, then panicked and brought about the collapse of the Asian economies. The IMF rescue packages are intended only to rescue the Western creditors. The Western financial industry, moreover, has been lobbying heavily for even more secure protection from future losses. One plan, put forward last year by the US and US Treasuries, envisions a $90 billion fund of public money, supposedly to avert currency crises. The idea is that G7 governments will, henceforth, underwrite the finance industry’s speculative ventures into emerging, markets before, rather than after, they turn sour. In this way, when bankers and fund mangers grow bored with a particular market, withdraw their funds and send the currency into a tailspin, they can collect on their losses immediately, without the tedious and time- consuming delays generated by IMF negotiations. The industry has also been working overtime to squelch defensive government action against their speculative attacks. At a recent conference in New York City, economist Jagdish Bhagwati noted that the IMF and the US Government, despite repeated crises and heavy criticism have intensities pressures on countries to lift exchange controls. The IMF recently proposed changing its Articles of Agreement so as to require countries to permit even more freedom for financial speculations. Echoing this sentiment, US Treasury official Lawrence Summers decried efforts by Malaysia, Hong Kong and other to curb foreign lending, calling capital controls “a catastrophe” and urging countries to “open up to foreign financial service” providers, and all the competition, capital and expertise they bring with them. Critics of IMF and US policy have, of course, noted that the combination of free flowing capital and bailout funds are a boon to banks other creditors. Such IMF critics as financier George Soros and Harvard’s Jeffrey Sachs complain that the game of international speculation and bailout played by the Western financial establishment- in which hot money rushes into a country, then pulls out, leaving behind a wrecked economy to be cleaned up by local governments and G7 taxpayers- is a menace to world economic stability. For the Western financial establishment, however, the bailouts are not the real prize. Nor are the devastated economies of Asia an unfortunate side-effect of a financial scamp. They are the while point of the game. Asia’s bankrupt businesses, insolvent banks and jobless millions are the spoils of what economist Michel Chossudovsky aptly calls “financial warfare”. The gains to be won from these financial hit-and-runs are immense. There are, first of all, the foreign- exchange reserves of the target countries. Countries accumulate currency reserves by running trade surpluses, often after year upon year of selling more abroad than they purchase. These surpluses are accumulated at great cost to the working populations, who labor hard to produce goods, destined to be consumed by foreigners. In 1997-1998, Asian countries spent nearly $100 billion in accumulated reserves trying- vainly as it turned out- to prevent devaluation. Brazil, the latest country to fall, spent $36 billion defending the real against speculators. Thus, in little over a year, did the Western financial elite confiscate $136 billion of hard-won wealth from the emerging markets. Next, there are the bargains to be had once the target country’s currency has collapsed and its firms are strapped for cash. Year of effort, for example, by the Korean elite to keep businesses firmly under control of state-supported conglomerates called chaebols were undone in a matter of months. By early 1998, as the IMF negotiated the terms of surrender, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs and other firms were snatching up ownership of Asian banks and industries. With currencies down 15-60 per cent and stock prices down 40-60 per cent, Asia is today a bargain- hunter’s paradise. Nor are assets the only bargains to be had. As a direct result of the destruction wrought by global financial interests, the prices of basic commodities have plummeted over the past year. Oil. Copper, steel, lumber, paper pulp, pork, coffee, rice can now be bought up by Western firms dirt cheap, an important key to the continued profitability of US industry. Then there is the higher tribune that countries, once in debt peonage to Western creditors, must pay on both old and new loans. South Korea, for example, under the terms of the IMF bailout, will pay interest on foreign loans that is 25-30 per cent higher that rates on comparable international loans- this despite the fact that the loans have been guaranteed by the Korean Government. Since the crisis began, international lenders have doubled or tripled the interest rates they charge on emerging- market debt. What is such usurious interest cripples the economy and drives the country into default? Well ,then they will become wards of the IMF, lender of last resort. Next, there are the people themselves, engulfed in debt, impoverished and committed by their governments to can endless course of domestic austerity and debt crisis of the 1980s, the Asian crisis has resulted in millions of newly unemployed, whose desperation will pull wages down world-wide. Like the debt crisis of the 1980s, the Asian crisis will turn entire countries into export platforms, where human labor is transformed into the foreign exchange needed to repay Asia’s $600 billion debt. In just this past year, Thai rice exports rose by 75 per cent, while Korea has managed to boost its exports and accumulate $41 billion in reserves for debt service. These figures, notes the World Bank, indicate that people in Asia “are working harder and eating less”. Finally there are the governments themselves, the ultimate prizes to be won. It is no accident that conditions imposed by the IMF, with their emphasis on altering state employment, welfare and pension systems, their insistence on reforming the legal and political systems of the target countries, entail a major loss of national sovereignty. Through IMF negotiations, national governments are transformed into local enforcement agents of transnational corporations and banks. IMF officials are quick to point out that the usurped governments often were not paragons of democracy and virtue. This of course is true. But the motives of the IMF are themselves profoundly undemocratic, intended to seize sovereignty and fix the rules of the game and to protect and expand, at all cost the wealth of the international financial elite.

How a market develops, including the orderly introduction of new instruments, is an important element of managing capital flows. In a broader since, the kinds of instruments available and favored (by the tax structure or by other regulations) in a market and the extent of foreign ownership allowed may also have an effect on the allocation of investment in the real sector. For example, in markets in which bonds are readily available or pension funds are impotent buyers, more capital is likely to be available for long- gestating projects. Two conclusions emerge from this analysis. First, capital flows are inherently neither good nor bad. They have a great potential to be either, depending on how productively they are used or on whether they are allowed to distort economic incentives and decisions. The contrast between growth in East Asia and stagnation in Latin America is instructive in this regard (There are significant exceptions to this generalization in both regions- the Philippines and other countries come to mind). Second, realizing positive benefits from capital inflows depends on sound macroeconomic and sectoral policies in the recipient country. Capital flows are a complement to good policy, not a substitute for it. The List of Literature. 1. Managing Capital Flows in East Asia. A world Bank Publication. Wash 1996y. 2. Private Market Financing for Developing Countries. IMF wash 1995 y. 3. The World Economy Global trade policy Edited by Sven Arndt and Chris Milner. Oxford , 1996 y. 4. International Studies Review Edited by ISA and Thomas S. Watcon Oxford Milner Sping 2000 y. 6. The Would Bank Research Program. The Would Bank Research. 7. Alan Greespon. Financial markets //New Internation-list. may 1999 y. c15-16 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||